Happy Birthday Sherlock Holmes: Learn How to Analyze Footprints

This weekend, fans of Sherlock Holmes will be celebrating his birthday. The legendary literary figure turns 159 this Sunday, January 6th.

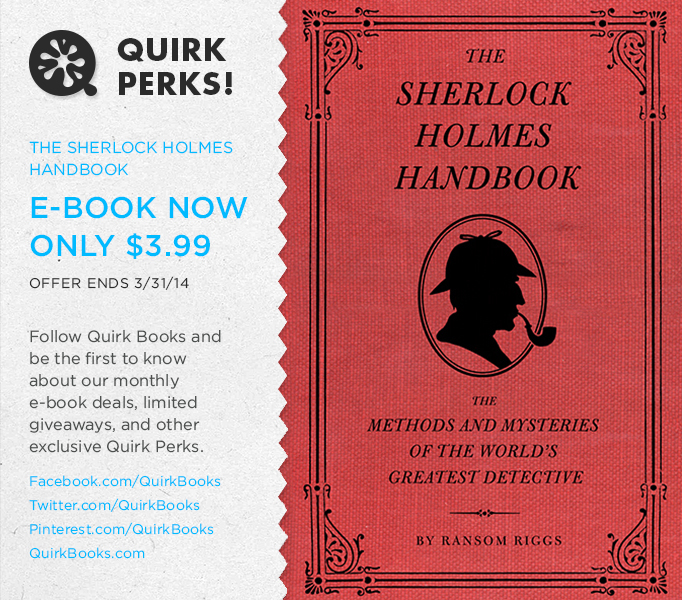

In honor of his birthday, here’s an excerpt from The Sherlock Holmes Handbook. Fun Facts: Ransom Riggs wrote this for us before he penned Miss Peregrine’s Home For Peculiar Children, and its full of illustrations (two of which are featured in this post) by Eugene Smith, the man behind the beautiful drawings in the Lovecraft Middle School series.

We’ll be giving copies away on our Facebook page, so make sure you check that out! Enjoy!

How to Analyze Footprints

“There is no branch of detective science which is so

important and so much neglected as the art of tracing

footsteps.”

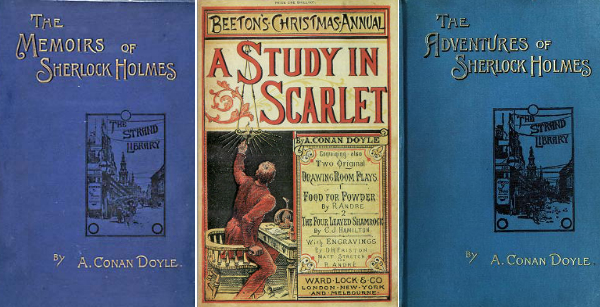

—Sherlock Holmes, A Study in Scarlet

A criminal may wear gloves to avoid leaving fingerprints at a crime scene, but, lacking wings, he cannot avoid walking through it. To the trained eye, footprints can be as distinctive as fingerprints: Holmes, the author of a monograph on the subject, could from examining a single set of tracks describe the probable height, weight, sex, economic status, and even the emotional disposition of the poor soul who left them, if not their owner’s very name. It follows that footprints and tracks are of paramount importance when investigating a crime scene.

• Search for footprints. Because one can only analyze footprints if there are footprints to be discovered, wet weather is a detective’s best friend. Mud and clay are ideal media in which to discover tracks of all kinds, not simply because they take foot impressions well but because they cling to one’s shoes, creating footprints where none may otherwise be found. Begin your search in any nearby soft-soiled garden beds or muddy lanes, then move toward the scene of the crime in a circular pattern to determine whether any prints have been tracked onto it.

• Follow the tracks. If they are fresh, your suspect may still be close at hand. Follow them—preferably with a pistol or police escort—and you just might find your perpetrator. Holmes and Watson follow a set of bicycle tracks over a muddy moor in “The Solitary Cyclist”—they know the direction the bike was traveling because the rear tire-track is a bit deeper—and come upon the cyclist himself, dead.

• Make a cast. Prior to commencing any serious analysis, it is vital to preserve a copy of the footprints in case anything should happen to them in the course of your investigation. Cast-making is an art unto itself—one with which Holmes, who has written about “the uses of plaster of Paris as a preserver of impresses,” is intimately familiar. Generally speaking, wet plaster is poured into the foot impression, hardened, and removed, providing a permanent record of the print (or wheel mark, hoof print, or paw print).

• Reconstruct the crime. There is much that footprints can reveal about the manner in which a crime was committed. Different sets of prints point to the number of perpetrators involved, whereas a great number of the same prints could mean the crime was premeditated; that the criminal spent considerable time at the scene, either lying in wait for the victim or plotting an escape after the deed was done. If there are but a few prints, however, you can be sure the perpetrator did not linger long, suggesting it may have been a crime of impulse or passion.

• Measure the length of the foot and stride. In A Study in Scarlet, Holmes judges a suspect to be quite tall by measuring the unusual distance between the left and right footprints, that is, the stride. Height can be corroborated by measuring the length of the foot impression: Generally, the foot composes about fifteen percent of an individual’s height. Dividing the length of the bare foot by 0.15 gives a rough estimate of its owner’s stature. (For shoe impressions, which add a bit of length, divide by 0.16.) What’s more, the angle of the feet relative to each other can be significant: “That left foot of yours with its inward twist is all over the place,” Holmes tells Inspector Lestrade while investigating a crime scene in “The Boscombe Valley Mystery.”

• Note the style and wear pattern of the shoe. A familiarity with sole impressions left by different types of shoes is helpful. In the same case mentioned above, Holmes was also able to ascertain that a suspect was fashionably dressed, judging from “the small and elegant impression left by his boots.” In much the same way, a terribly worn or out-of-fashion boot may indicate that a criminal is a pauper.

• Examine the depth and completeness of the footprints. Especially deep prints could mean a suspect was heavy or laden down with a burdensome object. The footprints of a running man will be incomplete, as Holmes observed in The Hound of the Baskervilles: What appeared to investigators to be the tracks of a man walking on tip-toes were actually, Holmes reasoned, made by a man “running for his life.”

• Match the footprints to a suspect’s boots. In “The THE SHERLOCK 36 HOLMES HANDBOOK Adventure of the Beryl Coronet,” Holmes ingeniously disguises himself as a tramp so that he may buy the cast-off shoes of a well-to-do suspect without arousing suspicion and is able to match them to footprints left at a crime scene.

BE AWARE: Footprints may be the most damning sort of track evidence, but they shouldn’t be focused on to the exclusion of all else. Giant canine tracks play a crucial role in Holmes’s solution to The Hound of the Baskervilles; cow and bicycle tracks in “The Priory School”; carriage tracks in “The Greek Interpreter”; and horse tracks in “Silver Blaze.”

Eric Smith

ERIC SMITH is the cofounder of Geekadelphia, a popular blog covering all-that-is-geek in the City of Brotherly Love, as well as the Philadelphia Geek Awards, an annual awards show held at the Academy of Natural Sciences. He’s written for the Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia Weekly, and Philly.com