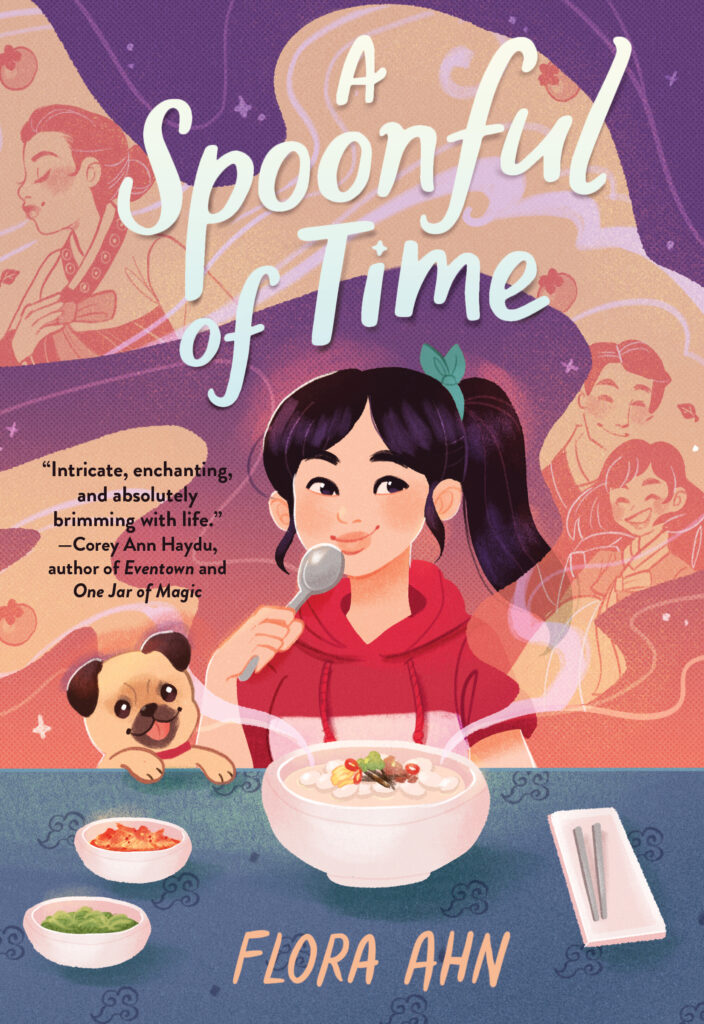

Flora Ahn Talks Lunar New Year, Food Memories, and Inspiration for A SPOONFUL OF TIME

The beginnings of A Spoonful of Time were hatched over the heat of a grill and amid aromas of beef, garlic, and onions. There was the idea for a story but it needed more details of Seoul from the past. So I turned my regular meals with my parents into research trips. Sometimes we would meet for lunch at a restaurant to eat steaming bowls of gomtang (beef bone soup) or bubbling jjigae (stew) in scalding hot stone pots. But most of the time we’d have barbecue at my parents’ house.

Every couple weeks I’d arrive at my parents’ house to find my mom slicing green onions and my dad painstakingly peeling garlic cloves, his one designated task that he both hated and took very seriously. Eager for the delicious meal, we’d flock to the dining room table. Following a swipe of butter on the tabletop grill, my mom would cook thin slices of onions and rib eye. We would dip the hot pieces of beef in a mixture of sesame oil, salt, and pepper and eat them with the green onions or wrapped in fresh greens with slices of peppers and garlic. We would eat until we were so stuffed we couldn’t eat another bite. But then my mom would cut up the leftovers and add a hodgepodge of things to make bokkeumbap (kimchi fried rice). And we’d eat until we were truly so stuffed we couldn’t eat another bite (at least until it was time for a dessert of fresh cut fruit). Throughout all of this, I’d pepper in questions to my parents about their childhoods in South Korea and food-related memories.

What did you bring with you to eat when you went hiking in the mountains of Seoul?

How did you store kimchi and doenjang (soy bean paste) without refrigerators?

Did you really use pine needles when making songpyeons (rice cakes stuffed with fillings)?

What were your favorite snacks and where would you buy them?

I learned how as young students they would stack their metal lunch boxes filled with rice, kimchi, and other banchan (side dishes) on the stove in the middle of the classroom to make them warm. I heard about how my mom would use her bus fare to buy her favorite crunchy snack, kwabaegi (twisted sticks of pastry), that she would crumble up in her pocket and eat slowly as she walked home. I found out that my dad’s entire family (of up to 10 at one point) would share one small hen for their samgyetang (chicken and rice soup). And sprinkled throughout they would add in random tidbits from their childhoods. How my grandfather would keep his dogs loose in their yard at night to keep away thieves and how one night they found one of their dogs pulling at the pants of a man trying to climb over the wall. How my grandmother kept all kinds of animals and when one of their newborn puppies got sick, my dad put the puppy in his shirt to keep him warm and ran all the way to the nearest veterinarian. Some of these made their way into A Spoonful of Time either directly or through inspiration or small details.

I take after my dad in that the smells and tastes of food strongly evoke certain memories. And with the lunar new year, my thoughts turn to my own memories of the traditions we followed each year for as long as I could remember. Unlike Maya, I was lucky that my family shared Korean culture with me and my sisters, even if they were modified to fit our American lifestyle.

Every new year I’d wake up in the early morning to the smells and sounds of bubbling beef broth in a large pot on the stove. It’s tradition among Koreans to eat tteokguk (rice cake soup) for the new year. My mom would soak the sliced ovals of rice cake the night before and wake up early to make the soup. While many families might have tteokguk for lunch or dinner, we always ate ours first thing in the morning, before my dad would have to go to work. As the owner of a convenience store, he worked on most holidays and rarely took days off. So, in order to continue traditions with our family, we started our day with a piping hot bowl of beef broth filled with soft and chewy rice cakes.

Each of us would top our bowls with however much sliced gim (roasted seaweed) and black pepper we wanted. I was heavy handed with both and my dad always criticized the amount of pepper I used and encouraged me to add more gim. We’d use our chopsticks to pick up the rice cakes until the soup became cool enough for us to slurp up. The table would be laden with a number of banchan in small bowls and freshly steamed and fragrant rice. We’d start the meal silent with our tiredness, but as we ate, we slowly grew more alert and would chat about our plans for the day and our new year resolutions.

After our bellies were full it would be time for sebae. My sisters and I would perform a deep bow all the way to the floor with our foreheads almost touching the ground as we wished them a happy new year – 새해 복 많이 받으세요. Our bows were clumsy and our Korean accents were terrible, but our parents would beam at us with pride and hand us crisp bills of money. After seeing my dad off to work, gathering in the garage doorway to wave goodbye, I’d help clean up and then head off to bed for a nap.

Now that I’m older and my dad has passed away, our traditions have changed slightly. My family celebrates the new year with tteokguk in the afternoon or evening. No need for an early breakfast at the crack of dawn. And gone are the hanboks (traditional Korean dress) as we now perform sebae in our regular clothes. I still bow to my mom, but I push away any money she tries to give me. And now I qualify as an elder to be bowed to by my niece and nephew. Having grown up as a youngest daughter, it’s strange to be in this elder position and to be the one handing out money. I try to keep a straight face, but as soon as they lower their heads to the floor, I laughingly tell them to get up as I pull crumpled bills from my pocket.

My family has changed over the years but the familiar aromas and flavors of tteokguk have stayed the same. And each bite reminds me of the past new years I’ve celebrated.

새해 복 많이 받으세요!