Quirky History: Weird Medieval Manuscripts

Of all the tens of thousands of manuscripts that were produced and copied during the Middle Ages, only a fraction have survived to our day. Some of these manuscripts are plain, written in black ink, and have no more than a few illustrations. Others are magnificent with colorful writings and illuminations plated in real gold. And then there are the manuscripts that are outright weird.

We would like to introduce you to four of the weirdest medieval manuscripts still in existence.

The Voynich Manuscript

The Voynich Manuscript gets its name from Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish book dealer who discovered this manuscript in 1912. The manuscript is written on parchment which has been dated to sometime between 1404 and 1438. What is interesting about the Voynich Manuscript is that it is written in an unknown language, using an unknown cursive script, both of which has yet to be deciphered. Attempts have been made to translate the book but nothing definitive has come from these efforts. There are even claims that Voynich himself created this manuscript and that it is indeed a forgery. The Voynich Manuscript is kept at the Beinecke Library at Yale.

The Devil's Bible

The Devil's Bible is in fact not a bible. However, it does contain the Christian bible as well as texts about how to perform exorcisms, calendars, the history of the region of Bohemia where it was made, and medical advice. The book was created in the 13th century and gets its name from the full-page portrait of the devil. Portraits of the devil are common place in medieval art. What makes this portrait unique is that the devil poses alone on the page and he is staring right at you. The Devil’s Bible is also known as Codex Gigas, or The Large Book. The reason for this name is that the Devil's Bible is the world's largest still existing medieval manuscript, weighing in at 165 lbs. The Devil's Bible is kept at the University of Uppsala in Sweden. The book was brought to Sweden after the Swedish army looted the city of Prague during the final stages of the Thirty Years War (1618–1648).

The Luttrell Psalter

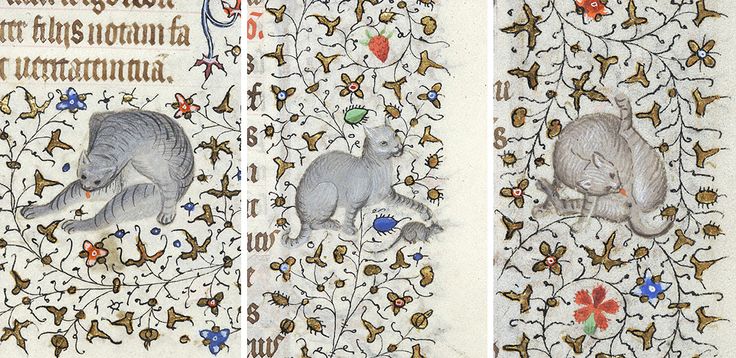

The Luttrell Psalter was created in 13th century England on commission by Sir Geoffrey Luttrell. The pages of The Luttrell Psalter are covered in surreal images that on first glance seem to make absolutely no sense. The images have been explained using theories about ergot poisoning and artists letting their imaginations go wild. However, scholarly analyses have shown that the images of The Luttrell Psalter are deeply rooted in the medieval tradition of the grotesque as well as in contemporary political satire. Moreover, the images are so-called visual puns, i.e., the artist takes the root of a word on the page as his starting point, and then he creates a visual pun based on that root. What makes these puns even more fascinating is that they function in three languages at the same time, namely Latin, English, and French.

The Crusader Bible

The Crusader Bible has nothing to do with the Crusades and it is not a bible. The book gets its name from Louis IX, king of France, who commissioned it. Louis IX (a. k. a. St. Louis, and yes, St. Louis, MO, is named after him) participated in the Seventh Crusade (1248-1250), hence the name The Crusader Bible. The book itself is a picture book, depicting scenes from mainly the Old Testament. Even though the scenes depict biblical events, the setting is medieval France. Because of this, The Crusader Bible is one of the most important visual sources to medieval chivalric culture. Moreover, because it is a picture book, during the course of the centuries, subsequent owners have added explanatory comments to the images. The result of this is that The Crusader Bible also becomes an invaluable source to language development, most notably 18th century Judeo-Persian, which is the hybrid language of the Jews of Persia, similar to how Yiddish became the hybrid language of the Jews of Eastern Europe.