Incredible Women in Science

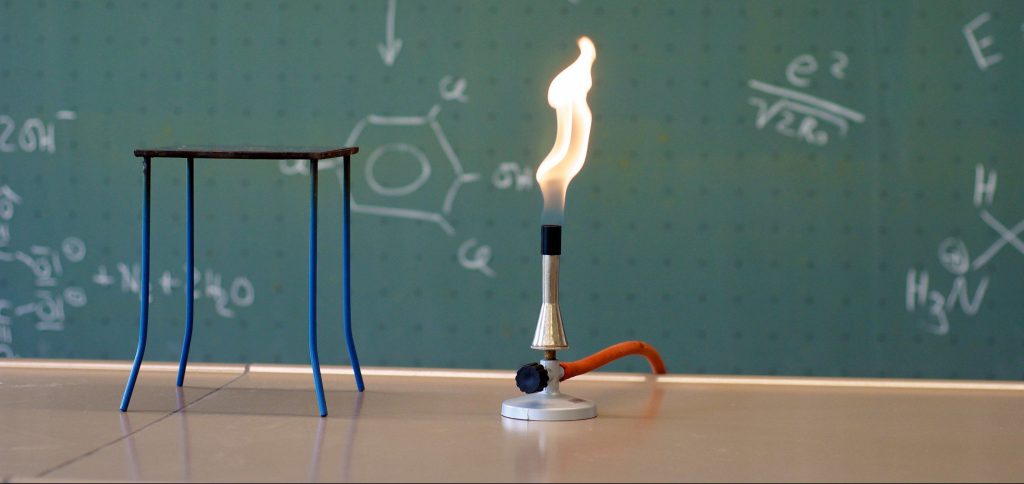

It’s German chemist Robert Wilhelm Eberhard von Bunsen’s 207th birthday on March 31—aka National Bunsen Burner Day. To commemorate the birth of the man who invented that instrumental piece of laboratory equipment, we’re highlighting some of our favorite scientists from Sam Maggs’ Wonder Women – women who broke down barriers, made significant contributions to the field, and, in a couple of cases, didn’t even get credited for their work. Today is for them.

Mary Sherman Morgan (1921 – 2004)

American rocket scientist Mary Sherman Morgan overcame some pretty insurmountable odds to become the scientist we know and love today. She started kindergarten at eight years old and almost didn’t attend school at all because her family forbid her from leaving their North Dakota farmstead. A social worker discovered this and immediately put her in school, setting her up with riding lessons and a horse so that she could transport herself to and from the one room schoolhouse. After graduating high school, Morgan ran away to DeSales College to study chemistry, secretly living with an estranged aunt. World War II cut her college education short and she turned to a factory job in Ohio – a job where she manufactured the chemical compounds for explosives! After the war, unemployment hit women hard. Determined to outsmart the job market, Morgan moved to California and began working as an analyst at North American Aviation (NAA), the organization that would later become NASA. She invented the chemical compound hydyne, effectively saving the space program and launching the country’s first satellite Explorer I. Of course, it was Explorer I’s designer Wehner von Braun who received all the credit, but Morgan’s son, George D. Morgan, never let the world forget her. He wrote a play called Rocket Girl, which was produced by Caltech in 2008. And when the play didn’t receive the reach he wanted, he wrote a 300 page biography about his mother in 2013 – Rocket Girl: The Story of Mary Sherman Morgan, America’s First Female Rocket Scientist.

Marie Equi (1872 – 1952)

Despite the fact that only 3% of American doctors were women at the time, Marie Equi moved to San Francisco in 1897 to study medicine at the Physicians and Surgeons Medical College and the University of California Medical Department, ultimately earning her degree in Portland in 1903. Equi went on to become an advocate for women’s suffrage, worker’s rights, and birth control. She was notably arrested with birth control activist Margaret Sanger in 1916 while the two of them were distributing pamphlets on “family limitation.” During the altercation, Equi stabbed her arresting officer with a pin as if to say, “Who’s the boss now?” She didn’t live to see Roe v. Wade in 1973, but her contributions to medicine and birth control advocacy sent a ripple through history, paving the way for safe and legal abortions, accessible and affordable birth control, and women’s autonomy over their own reproductive systems.

Lise Meitner (1878 – 1968)

Sam Maggs calls Lise Meitner “the most important scientist of the twentieth century you’ve probably never heard of.” And she’s right! In a bold move, Meitner’s father declared that each of his eight children – including Lise, born in Vienna in 1878 – would receive the same education, regardless of gender. It’s this progressive thinking that lead to Meitner becoming one of the first women to receive a doctoral degree from the University of Vienna, often the only woman in a room of over a hundred students. She then teamed up with chemist Otto Hahn, who would help her make incredible scientific discoveries in the field of nuclear physics, but (surprise, surprise) would also take complete credit for her work. And Meitner was a bona fide badass. She took a break from lab work during World War I to become an X-ray technician, at which point Albert Einstein called her Germany’s own Marie Curie. (Not that we need Einstein’s endorsement, but he knows what he’s talking about. Go Lise!) When World War II was beginning, Meitner’s Jewish parentage put her in danger of Hitler’s regime, so she fled Germany with the help of a team of fellow scientists. She set up shop in Stockholm and continued to correspond with her collaborator Otto Hahn. (Otto, by the way, didn’t help her escape Germany. But you already knew that, didn’t you?) After some incredible notes from Meitner, Hahn published their findings in the journal Nature with, you guessed it, Hahn taking full credit. And despite Lise Meitner coining the term “nuclear fission” in her own Nature article, Otto Hahn won the Nobel Prize for the theory, citing Lise Meitner as if she was a junior assistant. That jerk.

Alice Ball (1892 – 1916)

If you’re wondering why leprosy isn’t a medical concern any longer, you can thank chemist and medical researcher Alice Ball. After graduating from the University of Washington with two bachelor’s degrees – one in science and one in pharmaceutical chemistry, natch – Alice Ball went on to invent an injectable treatment for Hansen’s disease (aka leprosy). And she was only twenty-three! Sadly, Ball died the next year after suffering complications from inhaling chlorine gas in the lab. Ball’s inoculation went on to become the primary treatment for leprosy until sulfone drugs were invented in the 1940s. But here’s the kicker: Dr. Arthur Dean at the University of Hawaii took full credit for her miracle drug – even naming it after himself. That’s right, folks. This dude renamed our girl Alice’s invention “The Dean Method.” Read the room, Dean. That’s not okay. Not even a little bit.

Ogino Ginko (1851 – 1913)

If you love your female doctor, you partly have Ogino Ginko to thank. Ogino is responsible for opening the door for women to attend medical school in Japan. When her awful husband gave her an STD, Ogino was mortified that she had to receive such intimate treatment from a male doctor. And she wasn’t the only one! Many pregnant women in Japan avoided check-ups because they didn’t want a man examining their body – a fear that had a drastic effect on the lives of expectant mothers and their unborn children. Ogino graduated from medical school but graduating was only half the battle. The Meiji government, in an attempt to create higher health standards, created two tests that had to be passed before a doctor could begin practicing medicine – tests that women were not permitted to take. Ogino dug up historical precedent and argued that women should be permitted to take the National Physician Licensing Exam. And she won! Once she was licensed, Ogino wasted no time creating the Ogino Hospital in Yushima, a hospital specifically for obstetrician/gynecologists. She ran the hospital until her death in 1913.